They walked on Ninth Avenue, with Harvey and the two friends in front, his sister and her husband behind them. When they arrived at the restaurant, his sister was laughing about what had just happened on the street. “Do you know how many people just did the second take on you?” she said to her brother.

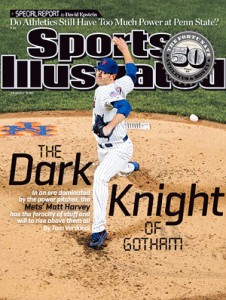

—Tom Verducci, Sports Illustrated, current issue’s cover story

Tom’s brother, Charles, had moved to New York [and] went to work as a caseworker with the New York City Department of Welfare. One day he walked into a tenement to visit a client. Charles saw a photo staring at him from the side of a refrigerator. “That’s my brother,” Charles said, a little surprised.

—John Devaney, Tom Seaver: An Intimate Portrait, recounting a story from 1967

Tonight’s snippet of movie dialogue I’ve fished from my subconscious and retrofitted to reflect the prevailing Metropolitan zeitgeist comes to us courtesy of the 1993 political comedy, Dave, a line uttered by Kevin Kline in the title role:

“It’s Harvey Day. Everything works on Harvey Day, OK?”

Friday was Harvey Day. And everything did work, didn’t it?

It was mostly Matt Harvey making sure functionality didn’t go out of fashion in Wrigleyville. He pitched the Mets to a win, he hit the Mets to a win, he willed the Mets to a win. He had help, but I’m going to assume it was generated by teammates who couldn’t bring themselves to let their ace down.

You only get so many Harveys in a lifetime. A Matt is a terrible thing to waste.

So would have been 7⅓ innings of two-run, five-hit ball, no-walk ball that should be draped with a bigger asterisk than any imagined for Roger Maris or Barry Bonds. If Ike Davis had made himself the slightest bit useful in the first inning and picked a wide but pickable throw from Ruben Tejada, half of Harvey’s runs don’t score. But allowing for humans being human — 24 non-Harvey Mets qualify under that heading — errors happen. Except Davis’s error, committed with Cubs on second and third and one out, was scored a base hit for Alfonso Soriano (with an error tacked onto Tejada’s ledger despite this perfectly decent throw) and one earned run became two. It’s the Chicago way, I guess.

But the Chicago way hadn’t come up against the Harvey way. They pull a home-cooked scoring decision, you pull an almost flawless shutout for the next seven innings. They send your ERA up a little, you send their batters back to the bench without mercy. So just to be clear, in real life, Harvey gave up only four hits and allowed only one earned run. It may not go in the books as such, but that was how it actually happened.

Listen to me fretting over the earned run average of a pitcher who can probably bear the burden of his number rising from 1.44 to 1.55 and not lose a whole lot of sleep. Look at me worried over whether Matt Harvey would go 5-0, stay 4-0 or be saddled with 4-1. Unless somebody’s in serious September Cy Young competition, I don’t pay more than fleeting attention to these kinds of details.

But this is Matt Harvey. I only get so many Harveys in a lifetime, too. I’ve been at this Mets fan thing for 45 seasons and I’m only on my third.

In the past decade, we’ve been occasionally blessed with an ace pitcher commanding games as if everybody else on the field is playing a supporting role in his drama. Pedro Martinez was that pitcher in 2005 and early 2006. Johan Santana was that pitcher during those intermittent stretches when he was healthy enough to be worth every penny of his enormous salary. R.A. Dickey was that pitcher to award-winning satisfaction last year. Hence, it’s not like we’ve been wholly deprived of aces. There is a tendency every time something brilliant crosses our path to forget that it’s not the first instant we’ve encountered something very much like it in the relatively recent past.

Yet Harvey is different. He’s a solid gold throwback to the platinum standards of Met acedom, just as he’s his own singular phenomenon. Some nights he’s another Gooden. Some days he’s another Seaver. Start after start, he’s Matt Harvey and all that’s come to imply. I’ve been careful to not go nuts with these comparisons, partly because it’s kind of lazy, partly because it’s still ridiculously early in his career, partly because it’s Seaver and Gooden, for goodness sake.

I’m willing to go there tonight, though, because Harvey was just so Seaverian against the Cubs. Not one-hit shutout Tom, but putting aside the bumpy first inning Tom and letting the opposing hitters know their fun for the day was over now.

And that was before the most beautifully Seaverian flourish of all kicked in: the helping of his own cause.

With Rick Ankiel on second in a tie game with two out in the seventh, the manager didn’t pinch-hit for his starting pitcher. Worst that could happen from that decision was Harvey would still be pitching in a tie game in the bottom of the inning. Best that could happen was Harvey would do what every starting pitcher is capable of but none of them seem to do anymore.

Harvey we know is capable, and Harvey, we had a pretty good hunch, isn’t the kind to leave his capabilities in a sock drawer. Matt thus singled Ankiel home when he absolutely had to break the 2-2 tie himself. It felt rare enough that Collins didn’t remove him in the first place. But to actually Help His Own Cause? I’m telling you, at that moment, I bought fully into the Seaver comparison because that’s exactly the sort of thing Tom would have done.

No, actually, that’s exactly the sort of thing Tom did. Three times as a Met starting pitcher, Tom drove in a run from the seventh inning on to break a tie he was nursing before going back to work to nail down his win. Once, in 1973, against the Astros, he did it with a squeeze bunt. The other two times were with home runs: off Ross Grimsley of the Reds in a 1-1 tie in the seventh inning in 1972; and off Bill Stoneman of the Expos in a 1-1 tie in the eighth inning in 1971. These were good pitchers late in games. But this was Tom Seaver, who could handle the bat as well as he could handle any lineup. Of course Gil Hodges was going to leave Seaver in. Of course Yogi Berra was going to leave Seaver in. (Mark Simon of ESPN Stats & Information let us know Met starters Gerry Arrigo, in 1966, and Sid Fernandez, in 1993, also drove in go-ahead runs late and went on to win their games.)

I want to say, “Of course Terry Collins was going to leave Harvey in,” but this isn’t 1971 or 1972. Almost nobody leaves anybody in to pitch, let alone to hit. Everybody has a standing conniption over workload and pitch count. But Collins, not necessarily the most innovative (nor most recalcitrant) of managers, understood who was best suited to butter his team’s bread Friday in the seventh. It wasn’t a pinch-hitter to face Edwin Jackson and it wasn’t a reliever to start the eighth.

Harvey, Collins affirmed later, “is a different animal.”

Granted, Matt wasn’t judged an exotic enough species so that when a runner got to second with one out in the eighth that Terry would do the sensible thing and keep faith in his ace. Harvey reluctantly came out, Scott Rice came in and — because Met aces since time immemorial tend to be starved for margin of error — David DeJesus singled to right. The hit sent baserunner Darwin Barney toward home with what seemed like the potential tying tally, the run that appeared destined to non-decision Harvey yet again…except the ball was retrieved and fired quickly and accurately by Marlon Byrd, and Barney couldn’t have been more out had being tagged by John Buck been his intention all along. Greg Burke and Bobby Parnell held the 3-2 fort from there.

No Met wanted to leave Harvey hanging. No Met wants to leave Gee, Hefner or whoever hanging, either, but this is a step up in class. Every fifth day, the 2013 Mets might as well be visitors from 1969 or 1986. Harvey makes their chances of winning that good. Wright homers into the wind. Murphy remains ablaze. Byrd channels Clemente. Parnell is calm and confident. Even Ike Davis eventually gets a base hit.

And Matt Harvey goes to 5-0.